The Community Preservation Act (M.G.L. 44B) was passed in September of 2000 and allowed municipalities to levy a property surcharge of up to 3% on real property and to create a Community Preservation Fund in which to deposit these funds. The money, which would be disbursed by the community’s CPA Committee, must be used for very specific purposes: to protect open space, preserve historic sites, and support outdoor recreation and affordable housing.

Communities have the option of levying the surcharge in 0.5% increments up to the maximum of 3%; communities who enact the maximum 3% rate are eligible for up to 100% matching state funds.

Those who levy between 1.5% and 2.5% qualify for an unspecified “match” from the state. The match rate varies from year to year as it is dependent upon “fees on filings at the registry of deeds and land court.” There are allowable exemptions for low-income persons and low- and moderate-income seniors. Veterans and their surviving spouses may also be eligible for an exemption. Municipalities can vote to exempt the first $100,000 of each taxpayer’s property. Shutesbury exempts the first $100,000.

A Fund Brimming with Unused Money

Shutesbury adopted the CPA by a sizable majority (75% for, 25% against) at its 2008 Town Meeting. The town elected to charge its taxpayers an additional 1.5% of their property value to be eligible for matching state funds.

Since 2009, Shutesbury has amassed $454,940 in its CPA fund. Subtracting this amount from the total amount raised over the last 12 years, $591,696, shows that Shutesbury has used only $136,756 from that account in that time. Tallying approved projects from 2011 through 2019 shows a total of $179,750. This reserve fund analysis prepared for the 2021 Town Meeting indicates that $44,774 has been set aside for unfinished projects--which is close to the difference between $179,750 and $136,756 ($42,994).

Limitations and Drawbacks of the CPA Tax

Though the CPA has helped Shutesbury save money, spending it has proven tricky. Over the years, the law’s downsides have become clearer.

The most obvious is the restrictions placed on the use of the funds. Another is that, by relying on registry fees to feed the CPA Trust Fund, money available from the state match will ebb and flow depending upon the level of recording activity at the registry. Since 2012, state budget surpluses may be added to the trust fund but those are equally unreliable.

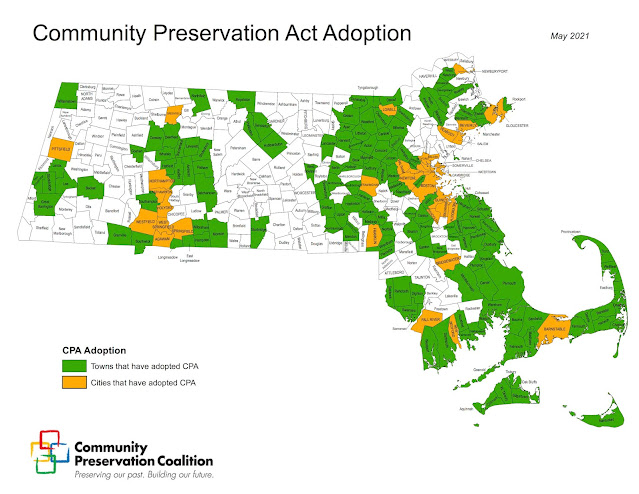

Since the trust fund is the same size regardless of the number of cities and towns adopting the law, the payouts decline as the pool of adopters grows. When Boston began receiving CPA matching payouts in 2019, a big chunk--$3.6 million--of state money was removed from the pool distributed to all adopters.

Another problem: The law favors wealthy communities. For municipalities accepting the maximum 3% surcharge, the state match is much higher--up to 100%.

All towns that adopted the CPA receive a “round 1” distribution in matching state funds from the Massachusetts CPA Trust Fund, an amount which consists of 80% of the Trust Fund’s total by the end of October. For municipalities taxing below the 3% threshold, disbursements stop after round 1.

The remaining 20% of Trust Fund money is reserved for communities that opted for the full 3% surcharge, amounts that are disbursed in two additional funding rounds. A study by the Kennedy School of Government and Harvard University in 2007 noted that cities and towns with higher property values tend to adopt a 3% surcharge, noting that communities on Cape Cod and in Middlesex County were big winners when it came to CPA matching funds.

For Shutesbury, the average state payout over the past 12 years is 28% of the amount taxpayers paid through the CPA tax.

The CPA also disregards Proposition 2 ½, which was enacted by ballot vote in 1980. When accepting Sections 3 through 7 of the law, which municipalities must do to adopt the CPA, they agree that the surcharge “shall not be included in a calculation of total taxes assessed”. This essentially allows communities to tax beyond the limit of Prop. 2 ½.

Can Shutesbury use more of the CPA funds it has on hand?

Currently, both Town Halls have mold problems. These buildings have historical significance and qualify for CPA funding.

The Old Town Hall has been a subject of concern for some time. The Select Board created a Records Storage Advisory Committee (RSAC) in June 2017 to make recommendations regarding the preservation of the town’s archival records. Discussions involved the conditions at Old Town Hall since that is where most records are stored. Moisture in the vault and main room where documents are kept were identified as major problems.

Although a member of the Town Buildings Committee was appointed to the RSAC as requested by the chair of the Buildings Committee, a draft report of the RSAC says that person “did not attend” meetings. The document later mentions that the Building Committee had the bricks in the Old Vault sealed as a barrier against moisture and suggested installing mini-splits to control humidity. That suggestion “languished” despite the fact that funds are available.

In May 2019, Town Meeting approved a $34,000 CPA project that would perform maintenance and repairs to Old Town Hall. The mold problem persists and has been cited as a reason why the building is unsuitable for community use. Perhaps CPA funding--for Old Town Hall and Shutesbury Town Hall--should be utilized to remediate the mold issues once and for all.

The money might also come in handy if the town decides to forgo a new library building and renovate and expand the existing one. CPA funds could be used to refurbish the existing, historic building, fix the heating system, and possibly pay to hook up to Town Hall’s well and septic. The Massachusetts Board of Library Commissioners offers grants for library expansion “on an irregular basis”, covering 45% to 50% of eligible costs.

Even without a state grant, Shutesbury could likely handle a library expansion project similar to the one proposed (and withdrawn) in 2001. Wendell borrowed $1.24 million in 2012 to build a new library and town hall. Assuming half that amount was dedicated to its 4,200 square foot library and using an inflation calculator, Shutesbury would need approximately $736,000 today to expand the current library by the same square footage. To date, the town has $514,000 earmarked for library construction.

It’s Time to Take a Break from the CPA Tax

It seems unreasonable to continue to tax Shutesbury property owners when the CPA fund is full of unspent money and there are no new projects on the horizon. The Old Town Hall project is the last on the state’s list and it appears there are no others on tap since the CPA Committee has not met since the spring of 2019.

The law requires a community that adopts the CPA to maintain adoption for five years, after which time it can revoke its acceptance by the same means it used to adopt the terms of the legislation. Until we can find eligible uses for the cash we have saved, perhaps we can consider repealing Shutesbury’s Community Preservation bylaw at the next Town Meeting.

Weekly Factoids:

Local governments in New England rely more heavily on property taxes as a revenue source than other U.S. states.

Source: The Lincoln Institute of Land Policy

Big-box stores have successfully used the “dark stores” assessment theory (the claim that the best comparable sales for chain stores are vacant or “dark stores”) in many U.S. states to significantly lower their property taxes, to the detriment of local governments.

Source: Bloomberg News